You are here

ANALYSIS: Coronavirus shutdowns don’t need to be all or nothing --study

Primary tabs

ANALYSIS: Coronavirus shutdowns don’t need to be all or nothing --study

Fri, 2020-11-27 09:53 — mike kraft Coronavirus lockdowns don’t need to be all or nothing | Science News Governments are implementing more targeted restrictions like limiting restaurant capacity to slow a fall surge. Research suggests they could work. Science News

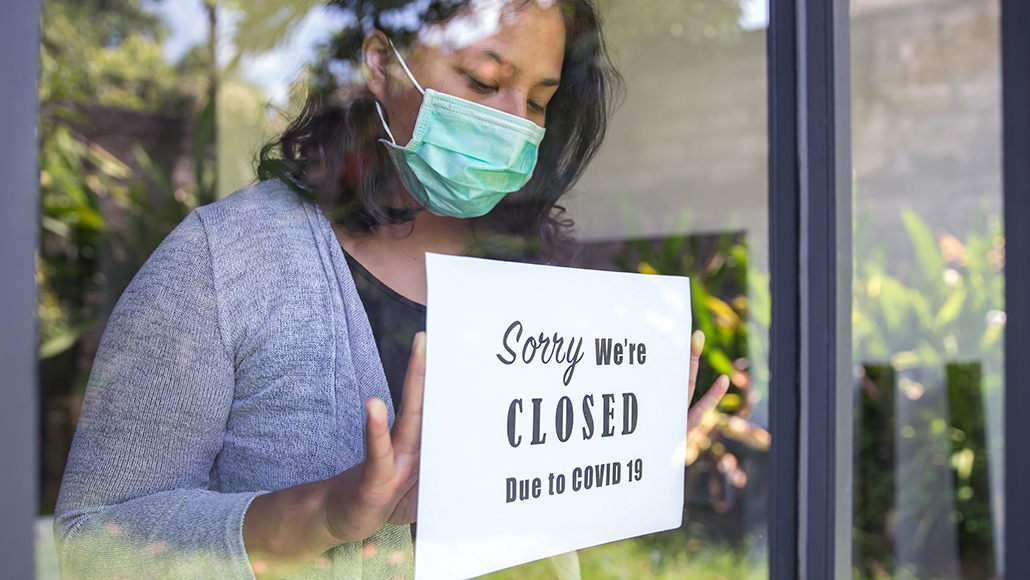

Coronavirus lockdowns don’t need to be all or nothing | Science News Governments are implementing more targeted restrictions like limiting restaurant capacity to slow a fall surge. Research suggests they could work. Science News As cases and hospitalizations reach record levels across Europe and the United States, leaders are being forced to make hard decisions about what to shut down and when. In the United States, President-elect Joe Biden has made clear that he won’t call for a national lockdown, but more targeted shutdowns at the state or local level are on the table. And in fact, many regions are already rolling out more targeted approaches, focusing on crowded spaces like restaurants, bars, or schools.

European countries began rolling out new restrictions in October, and in the United States many governors and city officials are beginning to partially clamp down. Public schools in New York City were closed on November 19; Minnesota has shuttered bars and restaurants for a month starting November 20; California officials enacted curfews between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. in certain counties through December 21.

Whether these fine-tuned restrictions will work remains to be seen. But scientists have been studying what worked and what didn’t in the early months of the pandemic, revealing some promising approaches. New research suggests that focusing on closing or reducing capacity at transmission hot spots while keeping less risky parts of the economy open can curb exponential rises in cases, while minimizing harm to the economy.

“We don’t need to fully shelter in place to slow transmission,” says Lauren Ancel Meyers, a mathematical biologist at the University of Texas at Austin. But these sharper approaches work only if governments set clear guidelines and people follow them, she says. Even the smartest interventions will be overwhelmed if enacted too late amidst rampant transmission within a community. ...

Early on, “no one had a clue as to how to stop the spread of the virus,” says Peter Klimek, a data scientist at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria. Instead, countries threw the kitchen sink at the virus, enacting many measures simultaneously.

Klimek and his colleagues used statistical techniques to try to disentangle which measures worked and which didn’t. In 56 different countries, including the United States, they assessed how more than 6,000 different interventions affected infection rates in the weeks after enactment. What they found comports with what we’ve since learned about the virus and how it spreads. ...

Recent Comments